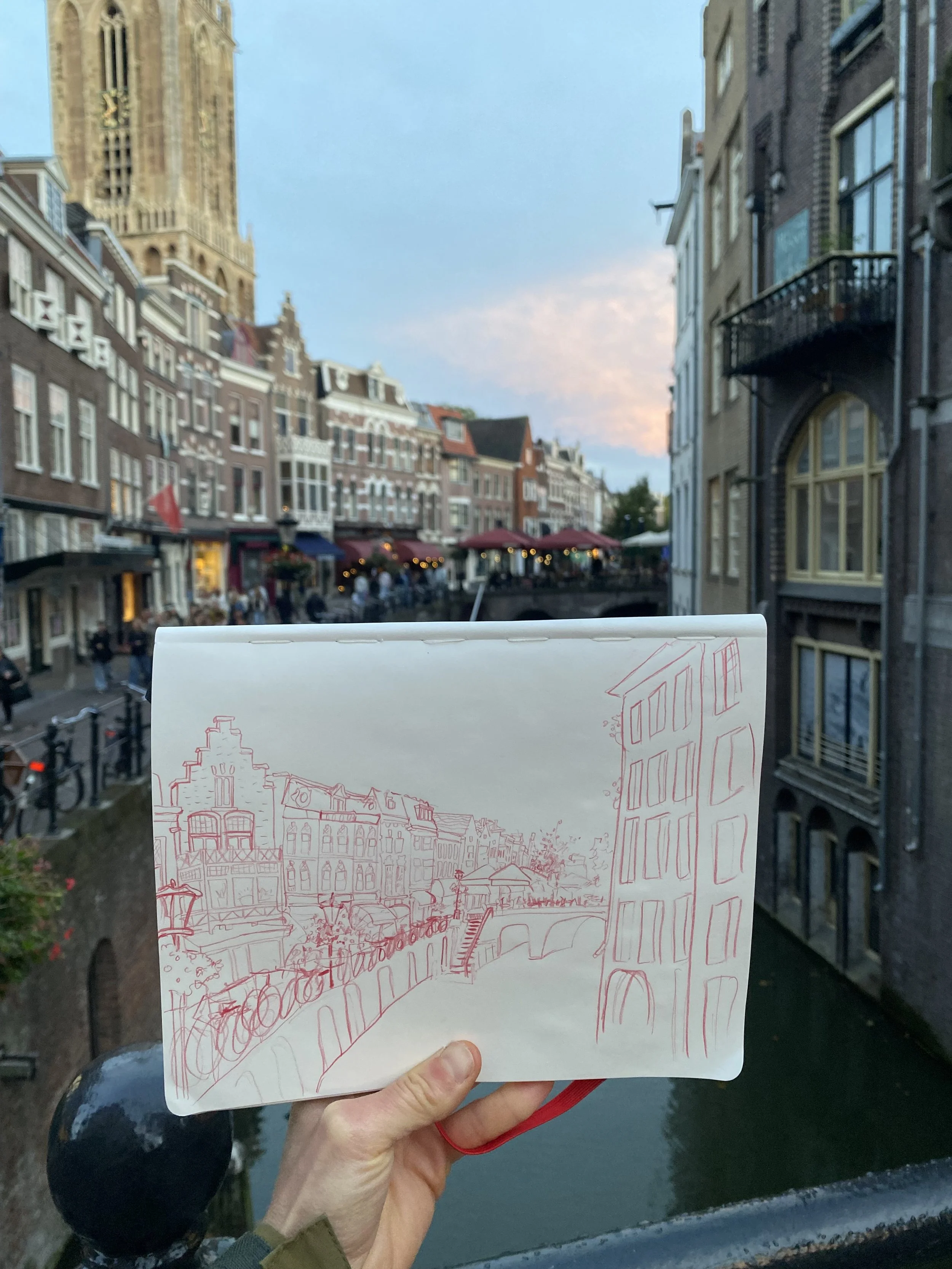

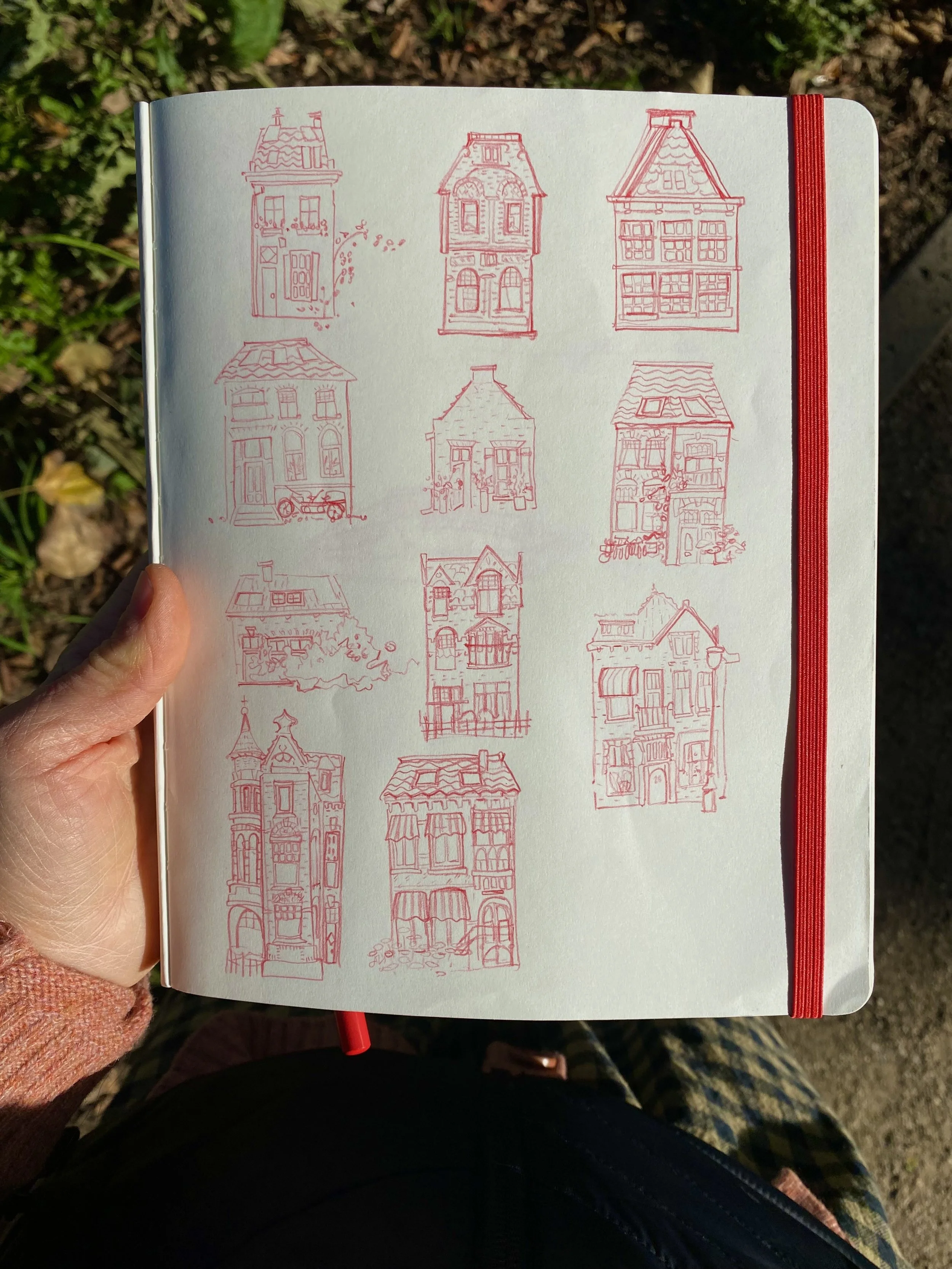

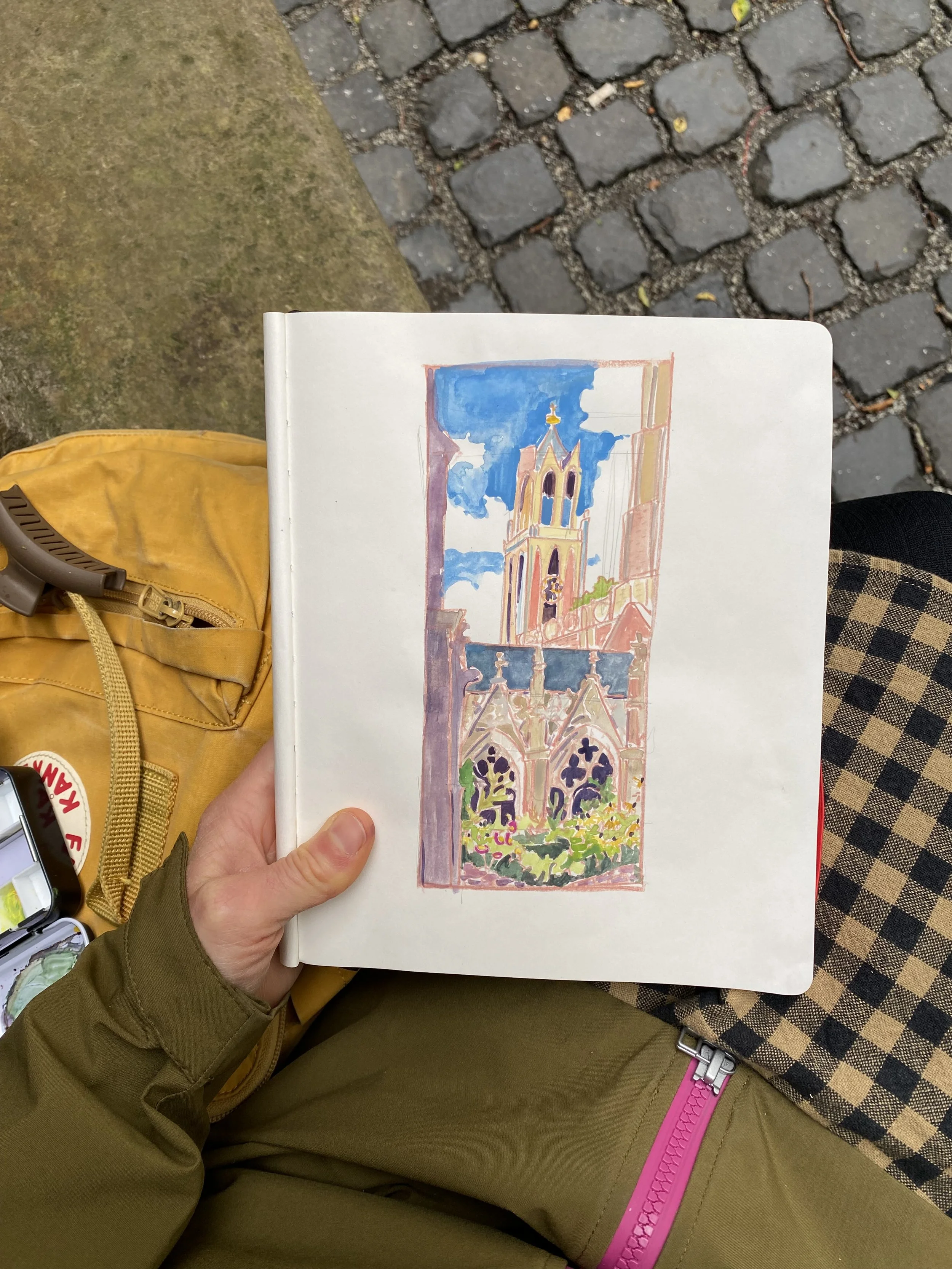

Solo Sketchbooking trip: The Netherlands

For one week this September I went on a solo sketchbooking trip in The Netherlands. I visited three cities: Den Haag, Utrecht, and Amsterdam. I hope you enjoy this little glimpse into my traveling sketchbook!

Den Haag

Utrecht

Amsterdam

Over these the last six months I have been working in a new body of work. I am finding it that it is centering around seasonality. I would love to be able to offer these works for sale, and yet I am finding something in me wants to keep them together at the beginning— I want to give the opportunity to speak to each other and grow into a kind of continuity and shape as the seasons shift one into the next.

Each piece is it’s own, and speaks in its own way. And yet as I consider them together I would like to imagine them being in a space together in a gallery exhibit in perhaps the next year or so. In light of that, I will be sharing some of the works in progress here on my website and other places, however they will not be for sale just yet. If one sparks your curiosity or interest please feel free to reach out to me to inquire about it for purchase next autumn or winter.

L’Abri

Greatham, Hampshire, England

April 26, 2023

Hey there,

I will be in England May 7 - December 9 2023, so I'll be taking a temporary hiatus from commissions an my own work here.

I am headed to English L'Abri -- a Christian community, a place of hospitality, conversation, work, study, teatime, and life together. If you are curious to know more you can find their website at https://www.englishlabri.org/.

Ever since I visited the Swiss L’Abri in 2016 for a few days, and worked as a Helper in the Rochester L’Abri in 2020, I have been wanting to attend a full term as a student. This year things lined up to be able to, and I am really looking forward to these next few months.

I am looking forward to a change of pace, time for reflection, and life together. I am coming with questions I want to explore, reading I would like to get into, and with the desire to cultivate friendship and grow in Christian community. And of course I will still be drawing and making. I hope and pray this venture forms me toward hospitality and community in deeper ways and that it finds its way into my artwork as well.

II also want to come with an open hand. I do not know exactly how these few months will shape me or what day to day life will feel like there, and I want to be open to how it unfolds.

Access to the internet will be sparce for the next three months, but I hope to occasionally share what I am up to art wise here and on my instagram, so if you would like to follow along feel free to find me there.

I will see you again in the fall!

Grace and peace,

Emily

Home holds warm yellow light and piano music

cradled in cupped hands

letting light and sound slip out through fingers

but slowly

just enough to stain the snow below the window

My feet crunch blue brown crystals of yesterday’s snow

I walk up the driveway

breath whistling in puffs.

Evening fades into blue and grey

and the cupped hands become more generous

spilling light recklessly onto the snow,

obliviously

scandalizing the outdoor world with

intermittent glimpsing into its evening

Lydia at the piano, mom chopping vegetables, Claire taking off her shoes

But the house doesn’t know

what it gives to the snowbirds, the icy footprints, and the occasional dog walker

Inside, it knows nothing but itself.

from The Wind in the Willows

by Kenneth Grahame

Chapter 5: Dulce DomumThe sheep ran huddling together against the hurdles, blowing out thin nostrils and stamping with delicate fore-feet, their heads thrown back and a light steam rising from the crowded sheep-pen into the frosty air, as the two animals hastened by in high spirits, with much chatter and laughter. They were returning across country after a long day's outing with Otter, hunting and exploring on the wide uplands, where certain streams tributary to their own River had their first small beginnings; and the shades of the short winter day were closing in on them, and they had still some distance to go. Plodding at random across the plough, they had heard the sheep and had made for them; and now, leading from the sheep-pen, they found a beaten track that made walking a lighter business, and responded, moreover, to that small inquiring something which all animals carry inside them, saying unmistakably, "Yes, quite right; this leads home!"

"It looks as if we were coming to a village," said the Mole somewhat dubiously, slackening his pace, as the track, that had in time become a path and then had developed into a lane, now handed them over to the charge of a well-metalled road. The animals did not hold with villages, and their own highways, thickly frequented as they were, took an independent course, regardless of church, post-office, or public-house.

"Oh, never mind!" said the Rat. "At this season of the year they're all safe indoors by this time, sitting round the fire; men, women, and children, dogs and cats and all. We shall slip through all right, without any bother or unpleasantness, and we can have a look at them through their windows if you like, and see what they're doing."

The rapid nightfall of mid-December had quite beset the little village as they approached it on soft feet over a first thin fall of powdery snow. Little was visible but squares of a dusky orange-red on either side of the street, where the firelight or lamplight of each cottage overflowed through the casements into the dark world without. Most of the low latticed windows were innocent of blinds, and to the lookers-in from outside, the inmates, gathered round the tea-table, absorbed in handiwork, or talking with laughter and gesture, had each that happy grace which is the last thing the skilled actor shall capture—the natural grace which goes with perfect unconsciousness of observation. Moving at will from one theatre to another, the two spectators, so far from home themselves, had something of wistfulness in their eyes as they watched a cat being stroked, a sleepy child picked up and huddled off to bed, or a tired man stretch and knock out his pipe on the end of a smouldering log.

But it was from one little window, with its blind drawn down, a mere blank transparency on the night, that the sense of home and the little curtained world within walls—the larger stressful world of outside Nature shut out and forgotten—most pulsated. Close against the white blind hung a bird-cage, clearly silhouetted, every wire, perch, and appurtenance distinct and recognisable, even to yesterday's dull-edged lump of sugar. On the middle perch the fluffy occupant, head tucked well into feathers, seemed so near to them as to be easily stroked, had they tried; even the delicate tips of his plumped-out plumage pencilled plainly on the illuminated screen. As they looked, the sleepy little fellow stirred uneasily, woke, shook himself, and raised his head. They could see the gape of his tiny beak as he yawned in a bored sort of way, looked round, and then settled his head into his back again, while the ruffled feathers gradually subsided into perfect stillness. Then a gust of bitter wind took them in the back of the neck, a small sting of frozen sleet on the skin woke them as from a dream, and they knew their toes to be cold and their legs tired, and their own home distant a weary way.

Dulce Domum

I love to walk about in a neighborhood at the evening time of the deep blue dusk. At that liminal time between evening and night the rich yellow light pours from certain windows along the street and houses briefly take on a different kind of life. It is a lucid moment when a house seems wrapped in its own introspection.

I first read Wind in the Willows only about three years ago, but since then I have read it several times. While it is not a book I grew up with, it has become a friend. Chapter 5, Dulce Domum, is especially bright to me because it gave words and story to something I have felt for some time.

On an evening trek home, Ratty and Mole walk through a town at dusk and glimpse into the life of some of the houses. Each house seems to enact a kind of unselfconscious performance for the two travelers. It is a curious performance where the actors – happily unaware of any audience – are being nothing more or less than themselves.

The rapid nightfall of mid-December had quite beset the little village as they approached it on soft feet over a first thin fall of powdery snow. Little was visible but squares of a dusky orange-red on either side of the street, where the firelight or lamplight of each cottage overflowed through the casements into the dark world without. Most of the low latticed windows were innocent of blinds, and to the lookers-in from outside, the inmates, gathered round the tea-table, absorbed in handiwork, or talking with laughter and gesture, had each that happy grace which is the last thing the skilled actor shall capture—the natural grace which goes with perfect unconsciousness of observation.

But it was from one little window, with its blind drawn down, a mere blank transparency on the night, that the sense of home and the little curtained world within walls—the larger stressful world of outside Nature shut out and forgotten—most pulsated.

In their introspection, the houses are in the strange position of being unconscious of their visibility. When we enter a house as a guest or a member the attitudes and relationships shift even slightly to accommodate to another participant in the web of relationships. However, at dusk, in a beautiful little trick of glass and light, we get the unusual privilege of a glimpse at life without our presence being acknowledged.

The light described in this passage also filled my imagination: warm yellow, orange, red light which seems to pour out of windows like water. At dark the light from windows is cooler and smaller, but at dusk it is a deep, thick, honey light. Window light and starlight and twilight come together each speaking in its own tone and language. The twilight speaks of mystery: both wonder and some fear as the knowable visible world around us grows smaller and more immediate. The early stars speak in an austerely beautiful way, yet they also lend hope and direction in the night. The window light is an invitation into warmth, companionship, and the comfort of the familiar. However, the invitation is only for those it knows and trusts.

Then a gust of bitter wind took them in the back of the neck, a small sting of frozen sleet on the skin woke them as from a dream, and they knew their toes to be cold and their legs tired, and their own home distant a weary way.

This sense of being drawn in and yet being an outsider also spoke to me. It is the sehnsucht, longing, the sharp pain and beautiful comfort of the here and not yet. Like many of us I believe, I also feel a desire to belong, a longing for home, a deep need to be present as myself in a real place. This is a longing which I have felt fulfilled in small ways here and now: when friends gather to play instruments together, in sharing conversation and tea from a teapot by our little Christmas tree, in a November Wind in the Willows feast. But this longing is an unquenchable thirst. It is a longing which will only come to fruition in the new heavens, the new creation, the time when I will be invited inside to be with Christ, to be myself, to eat and drink, rest and work, to be at home.

Firefly

This is the piece which began my exploration in my matchbox series. It started with the stars. A few weeks earlier I watched The Little Prince movie. For the most part, the movie was distinctly underwhelming when held up to the brightness of the book by Antone de Saint-Exupéry. However, I found some of the animation very compelling. At one point there are stars hanging by thread. It struck me how wonderfully strange this is.

When I think about stars, I often find myself in two minds about them. On one side they are peerlessly beautiful and fill me with wonder and awe. But alongside this awe I also experience some of their awe-full ness. Sometimes when I am out by a campfire, up on Colorado sand dunes, or in an Iowa prairie at night the stars seem so cold and somehow very frightening. They are so absolutely far away from me and from each other. Their inhospitable surface and inherent danger to our small human frame is overwhelming, and I have to look away.

Until very recently when light pollution made stars mere acquaintances they seemed to play an intimate role in people’s lives, forming the fabric of imagination. Growing up in the city stars are less familiar to me. I live in that unfortunate gap between the storied mystery and mythology of stars, and the studied scientific mystery of stars. I know only enough astronomy to make stars isolated and unfriendly distant objects. Beautiful, yes, but also unapproachable.

When I saw the stars hanging in The Little Prince I was overcome with the desire to make stars small as opposed to giants, held up by thread rather than moving in gravitational fields, kept in a container which fits in the palm of my hand rather than being a pinprick of light in a distant galaxy. I am interested in the tension between stars as inhospitable places, and stars as welcoming storied lights in a dark night. Somehow they are both.

A common thread in my recent work has been the search for place and belonging: that the poignant and sharp homesickness I experience both in places of deep community and deep isolation. For me, stars bring out this paradox of community and isolation, belonging and being a stranger as they house generations of communities’ stories and are yet coldly indifferent to human existence.

On the outside of my matchbox I have a little home with its lights on. It is an image for me which is both distant and welcoming, warm and cold, inviting and closed. This home is nestled into the paradox of stars: stars which are both above us and underneath us whether we can see them or not filling distant galaxies in which we have no part, and stars which tell deeply human stories around campfires with friends.

Matchbox Collection

Whatever is foreseen in joy

Must be lived out from day to day.

Vision held open in the dark

By our ten thousand days of work.

Harvest will fill the barn; for that

The hand must ache, the face must sweat.

And yet no leaf or grain is filled

By work of ours; the field is tilled

And left to grace. That we may reap,

Great work is done while we’re asleep.

When we work well, a Sabbath mood

Rests on our day, and finds it good.

– Wendell Berry

I have been returning to this poem by Wendell Berry often for the past year and a half or so. Snatches of it have run through my mind and give me courage. Largely thanks to Wendell Berry I have been thinking more about gardens. Many of the characters in stories I love are gardeners. Samwise Gamgee for one and Hannah Coulter for another. And even our first parents were gardeners. Tom Bombadill who is older than time thought highly of the hobbit Farmer Maggot, saying of him, “There’s earth under his old feet, and clay on his fingers; wisdom in his bones, and both his eyes are open.” (The Fellowship of the Ring). Growing things contain a wisdom and mystery which I will never understand, but I can enjoy nevertheless. There is a day to dayness together with transcendence, an earthy work and a heavily wonder: as in Adam and in us, there is a kind of dust and breath. “Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (Gen2:7). If I can extend the mystery of growing things to making I'll see what I can find.

Soil and Sight

Last spring when I was living in Waco, Texas, our neighbor Jim gave my housemates and I six young tomato plants. Jim is an avid gardener; in the spring he worked in his modestly sized but well tended backyard every day watering, digging, walking about examining his plants. He wore old jeans, heavy boots, and faded t-shirts. He didn’t talk much, but he cared for his garden. The day after he gave us the tomato plants he checked in with us to be sure we had planted them, for they would soon demand more substantial ground than the cardboard box Jim gave us. We hadn’t yet planted them and we resolved to do so that evening. Jim’s obvious care for his plants was contagious, so we did not take the job lightly. We dug the holes in a sunny part of our backyard, broke up the soil, planted our little green plants, and placed some wire tomato cages around them for support. We took care to water them a little every morning before the sun grew too hot, and then we waited.

“Vision held open in the dark”.

In her book Walking on Water, Madeline L’Engle talks about listening to the work, about serving the work even if we do not know where it will lead us. She says, “Sometimes when we listen, we are led into places we do not expect, into adventures we do not always understand. Over the years I have come to recognize that the work often knows more than I do.” As in a seed, there is a life in the work, prayer, and the tomato plant which needs to be listened to and a kind of knowing that suspends understanding. In planting, making, and in prayer we hold our eyes open in the dark with hope and expectation even as we move through mystery. L’Engle goes on to say that, paradoxically, before we can listen, we must work. It is exactly to this tension that Wendell Berry speaks to as well.

Work and Wonder

In his poem, Wendell Berry reminds me that I am an active participant in my work, study, friendship, painting, and prayer. Farmers and gardeners are some of the hardest workers I know. I am not a farmer, and my knowledge of plant life is small. As I read about Mat Feltner, Aunt Sarah Jane, and even wild Burley Coulter in Wendell Berry's fiction novels I know that I have never worked that hard in my life. Their work is strenuous, often mundane, repetitive, earthy. Though I know I’ve never worked like a true farmer, the process of making is likewise often difficult and slow. It is the tedious often unseen work—the thousandth edit, the hours of practice, the slow deliberate marks—which fill the artmaking process. Sometimes it feels like the success or failure of this work (art, friendship, planting, or prayer) rests squarely on my shoulders.

And yet at the turn of the poem Wendell Berry reminds me that there is a power beyond anything that we could ever do which unfolds young leaves, converts sunlight to food, and turns flowers into fruit. “the field is tilled / And left to grace”. We planted our tomatoes, weeded and watered, and yet I could never make the little light yellow flowers turn round and green and then red. Whatever fruit the Lord will bring out of my work, may I have the humility and the delight to know it is not of my own making. It is a mystery and a magic.

I can participate in the work and rest in the gift but that is not quite all. One warm day I took my sketchbook and watercolors out to our tomato plants and spent some time painting the young leaves and a little yellow flower which had recently emerged. I can work and rest, but I can also notice, investigate, and enjoy what I cannot understand. And this is also a gift.

don't the great tales never end?

“I wonder what sort of a tale we've fallen into?”

“I wonder,” said Frodo. “But I don't know. And that's the way of a real tale. Take any one that you're fond of. You may know, or guess, what kind of a tale it is, happy-ending or sad-ending, but the people in it don't know. And you don't want them to.”

“No, sir, of course not. Beren now, he never thought he was going to get that Silmaril from the Iron Crown in Thangorodrim, and yet he did, and that was a worse place and a blacker danger than ours. But that's a long tale, of course, and goes on past the happiness and into grief and beyond it - and the Silmaril went on and came to Eärendil. And why, sir, I never thought of that before! We've got - you've got some of the light of it in that star-glass that the Lady gave you! Why, to think of it, we're in the same tale still! It's going on. Don't the great tales never end? “

. . .

I have been re-reading (or rather re-listening to) The Lord of the Rings. As I listened to the brilliant voice of Rob Ingles read The Two Towers in the midst of processing these past few months Samwise Gamgee’s words struck me: in some ways we also hold onto a light in a story that has been going on since the beginning of time. “Don’t the great tales never end?”. I am afraid I do not know much about the history of the Silmarils but I do know what it feels like to be in a story bigger than myself and hold onto a light more powerful than anything I could make or do. Whether our days feel strange or secure, whether I feel at home or more like a wanderer, if events in the world or in my little circle of experience look dark I can take comfort in the light of the Silmaril and in a story that has been told before me.

“I think of the country as a kind of palimpsest scrawled over with the coming and goings of people, the erasure of time already in process even as the marks of passage are put down. There are the ritual marks of neighbourhood - roads, paths between houses. There are the domestic paths from house to barns and outbuildings and gardens, farm roads through the pasture gates. There are the wanderings of hunters and searchers after lost stock, and the speculative or meditative or inquisitive 'walking around' of farmers on wet days and Sundays. There is the spiralling geometry of the round of implements in fields and the passing and returning, scratches of ploughs across croplands.”

- Wendell Berry, from Native Hill

The “speculative, meditative, and inquisitive ‘walking around’” is what making often feels like for me. I pick up bits of dried plants, little scenes jotted in my sketchbook, a color, or a turn of phrase. For me it is a little like attentive wandering. I hope these give you some of the pleasure, wonder, and searching it gives me.